By Caleb Hannan @calebhannan on X

Nov. 17, 2023

Last week, Hindenburg Research published a long report on EHang Holdings Ltd. (Nasdaq: EH), a Chinese-based, U.S.-listed eVTOL start-up.

EHang makes pilotless passenger drones it hopes will become the basis for an entire new industry of low-level air tourism and much more, including a future where it’s as easy to take an air taxi in a big city as it is to call an Uber.

Hindenburg’s report came out at a time when we at Sharesleuth were preparing our own investigative piece on the company, including a look at the veracity of EHang’s claim to have some 1,300 orders. Rather than spend too much time on duplicative material from Hindenburg’s thorough report, we will focus on other areas that investors might want to consider.

The first comes in the form of EHang’s company culture, which former American employees told us was always about moving fast and paying little attention to certain social or ethical norms. The second relates to the safety of EHang’s 216 — its flagship, two-passenger autonomous drone which recently made history by receiving approval from the Chinese equivalent of the Federal Aviation Administration, for limited commercial use.

Some industry observers say that milestone might only have come because of EHang’s willingness to cut corners, reminiscent of other failed attempts at chasing history. More than one even drew a parallel to OceanGate Inc.’s Titan submersible, which imploded on an underwater journey in June, killing the company’s founder and four passengers.

Sharesleuth gave EHang multiple days to answer a written list of questions; it has not responded.

(Disclosure: Mark Cuban, owner of Sharesleuth.com, has a short position in EHang’s shares. Caleb Hannan, who wrote this story, and Chris Carey, editor of Sharesleuth, have no position, short or long, in the company’s shares.)

Company Culture

The insight on EHang’s culture comes from multiple former employees of its now-shuttered U.S. subsidiary, which was based in Northern California. Primary among them: A woman named Amy Covington.

The following narrative comes from conversations with Covington, some of her former co-workers, and a lawsuit she later filed and won. Although she only worked for the company for a few months nearly eight years ago, we believe her experience, and that of her onetime colleagues, is instructive in assessing the credibility of EHang today – especially in light of our other findings, many of which have already been made public in Hindenburg’s report.

Covington was a marketing manager from Minnesota when she was first approached by EHang to be its creative director. She was enticed to join, she says, by the offer to build her own team and receive equity in a growing start-up with big ambitions.

She was told that initially she would be provided with corporate housing. But when she arrived in the San Francisco area, she instead found a decrepit mansion where she ended up sharing a bathroom with a young, male American subordinate who was just as baffled by the circumstances as her. The other occupants of the home included a rotating cast of Chinese engineers who she and others say smoked constantly and never cleaned up after themselves, leading to constant pest problems.

Shortly after she started at EHang, Covington was introduced to its founder and chief executive, Huazhi Hu. Covington already was on edge, being the only American woman in the house and previously being told, in an introductory lunch with her boss, that if she wanted to never work again in her life someone as pretty as her could easily marry a rich Chinese man.

(Covington and EHang’s 184 at the 2016 Consumer Electronics Show, courtesy Amy Covington)

When she first met Hu, she alleges, he was walking down a line of American employees, introducing himself. He stopped in front of her and asked her through a translator how old she was and how many kids she had. Hu, she says, seemed to take an interest in her right away, a claim backed up by multiple other former EHang employees who were present at the time.

Later that night, according to her lawsuit, Hu pulled her aside at a restaurant during a senior leadership meeting and, while looking her up and down, told her that he really liked her. She says she walked away immediately. The next morning, Hu stood by her desk and tried to talk to her through two other female employees, who he asked to translate for him. According to Covington, these employees, who knew her, were too embarrassed to translate what Hu was saying. They later told her the gist of his comments were that he liked Covington’s body and was surprised at how fit she was, given that many Americans were so fat.

On the last night of his first visit to the American office, Covington says Hu stroked her hair unexpectedly, and told her boss that he’d done so because he wanted to see if its color would come off on his hands. Later at dinner, Covington says that EHang’s then-chief financial officer bragged about how Hu had made his first million at age 19, and that men like him in China would pay Covington that much just to touch her.

Despite the unwanted advances from the founder and CEO, Covington still had a job to do. Which itself was a problem.

EHang’s only product at the time was a consumer drone called the Ghost. According to Covington and other former EHang U.S. employees, the drone was wildly unpredictable.

Early reviews were bad and Covington and her co-workers were constantly fielding angry customer calls and emails. Employees were encouraged to buy the product themselves and write favorable reviews to offset the negative ones, even going to the trouble of doing so somewhere other than EHang’s run-down mansion headquarters, so that Amazon wouldn’t recognize the IP address.

When Covington and others told EHang senior leaders that they should delay the launch of the drone’s second iteration in order to fix bugs, she says they were berated. Former employees say the Ghost had a mind of its own, constantly crashing into the hills that surrounded the San Carlos mansion, coming down perilously close to the highway that ran near the company’s Chinese headquarters in Guangzhou, or, in one case, going high into the rafters in a convention building in Germany, raining plastic and heavy battery parts down on unsuspecting visitors at an international toy fair.

The flippant regard for safety even caught up with Hu.

During that first trip to America, multiple former employees say that they warned Hu not to play with the Ghost inside the mansion, because of its unpredictability. Hu, they say, insisted.

At one point the founder and CEO found himself operating a Ghost that, with no apparent reason whatsoever, went to full throttle and flew right towards him. The result was a lost chunk of his finger, a spurting stream of blood, and employees shocked to find Hu laughing off the injury.

(CEO Huazhi Hu after being bandaged, photo courtesy of Amy Covington)

Covington and others could see that even the revamped, second-generation Ghost drones were often put together with parts from competing companies — a fact that disturbed them but seemed not to be a concern for EHang executives.

They also knew that EHang wasn’t shy about pretending its product had the same capabilities as those of other companies. Covington says she was encouraged to make up product specs on marketing materials, copying those of more established drone makers like DJI — a vastly more successful Chinese rival — instead of actually putting the Ghost drone’s true capabilities on paper.

Covington once tried to set up a press demonstration for a site called TechCrunch. She was minutes away from greeting the reporter at a park in San Francisco, she says, when the Ghost unexpectedly flew off into a lamppost. Scrambling, her team tried to operate another Ghost they’d brought with them. It too went off in the wrong direction and crashed. Covington says she canceled the event at the last moment.

Another former employee who spoke with Sharesleuth says they were responsible for putting together promotional videos like this one:

The video, this employee says, was shot entirely using a DJI drone, at the behest of Hu and others within EHang. On its YouTube page, EHang published it with the caption “Short video highlighting some of the unique shots we got over the last 6 months using the #GhostDrone.”

“I felt so wrong doing that,” the former employee told Sharesleuth.

To Covington and other employees, appearances seemed to matter much more than reality. The team finally left the mansion and moved to a relatively lavish space that seemed capable of housing 70 employees, far more than the 15 that worked for EHang’s U.S. subsidiary.

When Covington and other employees asked about the discrepancy, they allege they were told by management that the whole point was to generate media and investor excitement and give the perception of a company doing much better than it actually was.

Covington says that the attitude towards her from her bosses in America also shifted perceptibly after she rejected Hu’s advances. She says she was put in an impossible position of trying to get favorable coverage of a product that at its best worked just OK and at its worst was dangerous to use.

Covington organized the company’s booth at the 2016 CES (formerly Consumer Electronics Show) in Las Vegas. There, EHang displayed its first-ever autonomous passenger drone, the 184, and Covington said many in the company considered the event a big success.

Not long after, however, Covington says she was fired without notice or severance.

Roughly two years later, EHang’s U.S. subsidiary filed for bankruptcy, at the same time as another subsidiary in Germany. In the interim, Covington had filed suit against EHang for wrongful termination. She also asked to receive what she was owed in vested equity.

Covington was awarded a default judgment of $700,000. But because of the company’s bankruptcy, that judgment was stayed. Ultimately, she says, she walked away with only $8,000 in unpaid wages after taxes.

Her former boss, Gary Wang – who she alleged had made the initial comment about her ability to land a rich Chinese husband – did much better. In a lawsuit first filed in 2020 for breach of contract and unpaid compensation, Wang claimed that EHang, and specifically Hu, had repeatedly rebuffed requests to issue him company shares that had vested during his employment.

Those shares would have proved exceptionally valuable. EHang went public on the Nasdaq in December 2019, selling $40 million of American Depositary Shares at $12.50 each. The stock price stayed in that range until late 2020, then went almost vertical, peaking at more than $120 a share in early February 2021. That was just after the company submitted its initial certification request for the 216.

EHang’s shares plunged by more than 60 percent after Wolfpack Research raised questions about the company and its main Chinese customer. They remained on a downward trajectory for most of 2021 and 2022, dropping below $4 last October. Then the stock took off again, hitting $16 in January, $20 in July and $25 last month, when EHang announced the favorable certification decision. The closing price Thursday was $14.38, giving the company a market capitalization of almost $870 million.

In 2022, a jury awarded Wang a total of $18.5 million to be paid by EHang and Hu. This past April, the company announced it had settled Wang’s claim with a $3.375 million payment.

(From Page 138 of EHang’s most recent Form 20-F)

Product Safety

Covington and former employees have strong opinions about the safety of EHang products. They witnessed firsthand the unpredictability of the Ghost drone. And since then, they’ve watched with a mixture of fascination and horror as the company continues to build ever-larger products designed to hold more people.

In the electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing industry, EHang has distinguished itself not only by the speed at which it achieved some amount of regulatory approval, but by a difference in design and use case. Whereas its U.S. and European competitors have focused primarily on first building piloted small aircraft meant to replace helicopters and airplanes on short flights, EHang’s most prominent design is much smaller, lighter, and less expensive, seemingly aimed at providing an urban air-taxi experience today that others insist is years, if not decades, away from being safe and cost-effective.

(Graphic from a recent EHang speech comparing eVTOL products. The company’s flagship, the 216, is number seven.)

Everyone Sharesleuth spoke with who once worked at EHang has been adamant that they would never take a flight in any EHang product. They describe an ad hoc system of hobby-grade hardware and software, some details of which were well covered in a separate activist report from 2021 by Wolfpack Research.

Yet Hu and the company insist that safety is their top priority.

On Oct. 13, when the Civil Aviation Administration of China, China’s FAA, approved EHang’s 216 for limited commercial use, the company talked about the lengths it had to go through to gain approval, including 40,000 test flights.

EHang’s press materials routinely describe a long, methodical process of slowly satisfying regulatory standards. For all that talk, however, one thing EHang hasn’t made clear is how it’s actually flying its drones.

An executive recently said that while EHang’s hardware is “quite sophisticated, the real rocket science is in the software.” We asked a Mandarin-fluent researcher with experience in the eVTOL world to review the company’s recent regulatory filings. Nowhere in that document, this researcher says, was there an indication of what kind of software EHang uses to run its flights.

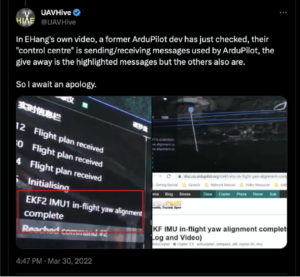

That question has become a hobby horse for online UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) experts. People like Ian Hudson, the man behind @UAVHive, who’s been quoted extensively before in places like the BBC and The Guardian.

Last year, Hudson thought he caught EHang in a lie. He and others have often observed that in EHang’s own promotional videos, the company seems to give away evidence that it’s using a piece of open-source software called ArduPilot.

For people who know little about UAVs, the significance of these online fights can easily be lost. According to conversations with Hudson, other UAV experts, and even ArduPilot developers, the simplest way to put it is this: critics believe that EHang may be using a product that’s not meant for manned vehicles.

ArduPilot’s rules aren’t up for debate. It says so right in the software’s Code of Conduct:

On X (formerly Twitter) last March, Hudson documented what he saw as a clear violation of this conduct, screenshotting ArduPilot-specific language on a control center from EHang’s promotional video, one of many such examples that he’s compiled.

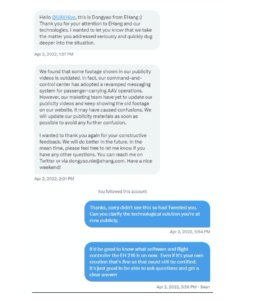

Confirmation came in the form of a direct message from EHang’s then-media relations person Dongyao Nie. (Hudson says he normally would not share a private DM if the issue at hand didn’t pertain to a possible immediate threat to public safety.)

But Nie and the company insisted that the screenshot was from old footage that was accidentally inserted into a new video. While they acknowledged what they claimed was a fixable mistake, neither Nie nor EHang ever answered Hudson’s follow-up question about what software the company was using if it wasn’t ArduPilot.

That question still hasn’t been answered today.

When reached by Sharesleuth, ArduPilot project manager Craig Elder was measured and reserved about what risks EHang might be taking. Elder says that it is common knowledge that EHang’s eVTOL competitors often go through much more formal channels to procure rigorously stress-tested software to use on their own products.

EHang, he acknowledges, is likely pursuing a different strategy than its biggest competitors like Archer Aviation Inc. (NYSE: ACHR); Joby Aviation Inc. (NYSE: JOBY); or Volocopter, a privately held company that hopes to provide air taxi services at the 2024 Paris Olympics.

Indeed, our review of SEC filings found that EHang has spent only about $100 million on direct research and development since the start of 2017. Archer reported spending $197 million in R&D in the first nine months of this year alone, while Joby reported spending $265 million.

Elder says the ArduPilot development team is aware that EHang has used its product in the past. He says that at one point developers from EHang did reach out to ArduPilot to ask some questions, but that he hadn’t heard from anyone at the company in years.

Back then, EHang insisted to him and ArduPilot that it was only using the software on unmanned vehicles. Elder stressed that despite the code of conduct, ArduPilot is “extremely robust, extremely capable, and extremely configurable.” He also made sure to note that ArduPilot had long since outgrown its status as anything close to hobby-grade quality, and was in use, currently, in drones operated by established institutions like the UK’s Royal Mail.

But in talking with experts in the eVTOL and UAV field, one thing cropped up consistently: people who have high hopes for this industry are scared of a big, literal crash. The fear is that all of the work that has gone into painstakingly meeting safety standards could be undone quickly by any company that doesn’t always adhere to those same standards.

More than once during reporting, experts brought up the specter of the Titan, a miniature sub that imploded in June on its way to the Titanic wreckage, killing five people, including its developer, a man with a seemingly devil-may-care attitude towards safety. Towards the end of our conversation about a company that may or may not be using software he’s helped build to do a job it’s not intended to do, so too did Elder, a man who also has experience with submersibles.

“The parallels to Oceangate [Titan’s owner] are real,” he said. “The consequences of failure far exceed the consequences of success.”

Chris Carey contributed to this report @sharesleuth on Twitter